Esther Pissarro

Laforgue, Jules, Lucien Pissarro, and Esther Pissarro. Moralités légendaires. London, England: Eragny Press, 1897.

Esther Pissarro (1870-1951) was a printer, designer, and wood engraver. She and her husband, fellow artist Lucien Pissarro, were members of the Arts and Crafts movement in England. Esther was the daughter of a London Jewish merchant and studied at the Crystal Palace School of Art. Esther and Lucien ran the Eragny Press, where Esther would both create and assist with wood engravings for book illustrations based on Lucien’s designs.

One of the most famous renditions of Ophelia’s death during this period was an 1852 painting by John Everett Millais. Ophelia is surrounded by a plethora of flowers and greenery representing faithfulness, chastity, and death. In this painting and similar contemporary works, Ophelia’s youth and virginity are juxtaposed with her death, depicting her tragedy as hauntingly beautiful. The model for the Millais’ painting was Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal, wife of Pre-Raphaelite artist and author Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Siddal was an artist in her own right and created sketches, drawings, watercolors, and oil paintings. For his painting of Ophelia, Millais required Siddal to pose in a bath full of water for more than four months. Although the water was kept warm by lamps underneath the tub, she contracted pneumonia and almost died. From this accident, Siddal became dependent on laudanum, and in 1862 she died from an overdose. Although Siddall was a painter herself, she is often remembered as the tragic muse for many members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

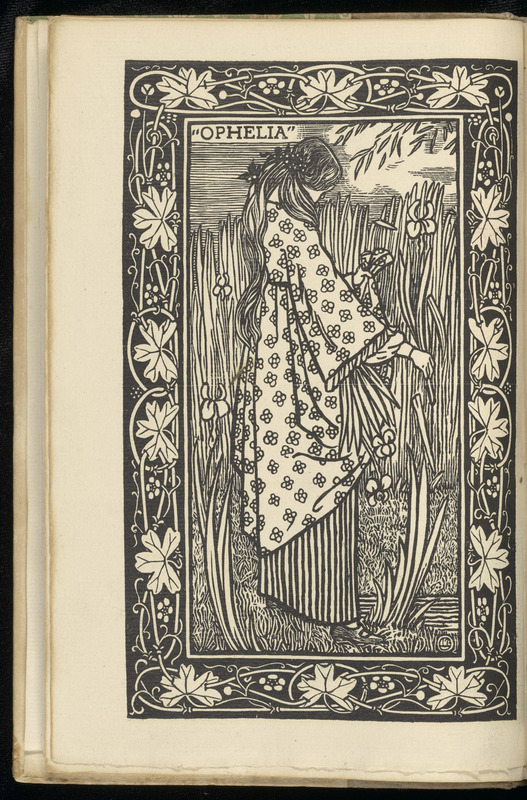

The Pissarro wood engraving of Ophelia shows the maiden by the water, picking some irises (representing death), with her head down and face hidden. The scene is beautiful without having to articulate Ophelia’s own feminine beauty. Ophelia wears a garment evocative of Japanese kimonos, reflecting the popularity of japonisme in Europe and the United States at the time. Here Ophelia’s death is only alluded to, rather than explicitly depicted, in contrast to Millais’ painting. Male artists often depicted Ophelia after her drowning, practically burying her in foliage. Similarly to the Lady of Shalott, Ophelia is most often depicted by male artists as a beautiful and passive dead woman, only to be gazed upon as an object. In this way, she loses her personhood and identity. However, Pissarro depicts Ophelia standing, positioned in the center of the composition, present and alive.