Ann Alexander, Dorothea Braby, & Sara Hawks Sterling

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Prose Translation. London: C. Sandford at the Golden Cockerel Press, 1952.

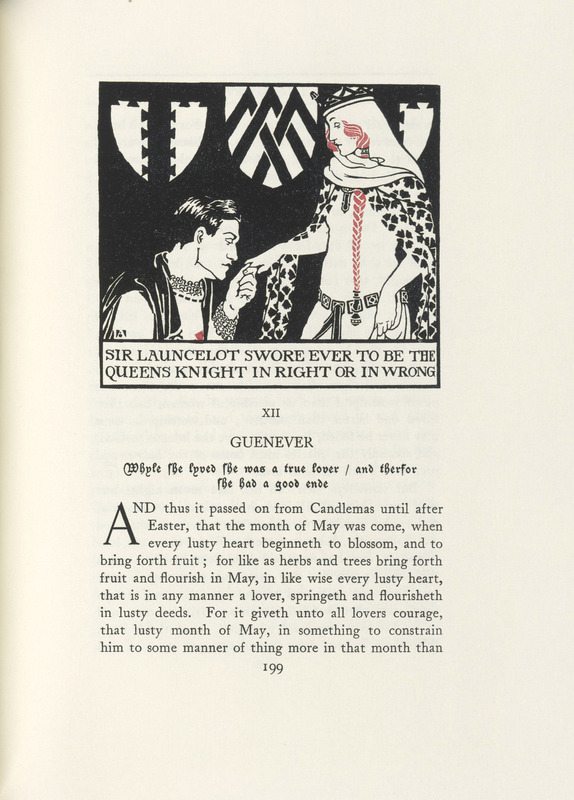

Malory, Thomas, and Ann D. Alexander. Women of the Morte Darthur: Twelve of the Most Romantic of the World’s Love Stories. London: Methuen, 1927.

Sterling, Sara Hawks., and Clara Elsene Peck. A Lady of King Arthur’s Court: Being a Romance of the Holy Grail. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1907.

These examples in the early twentieth century show the continued appeal of Arthurian themes to women artists. Each artist engages with popular Victorian medievalism in their book bindings and illustrations. Outside of illustration, these examples also showcase how women were not just engaging with Arthurian literature but adapting and revising it according to their own terms. Ann Alexander focuses an entire text solely on the women of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Alexander’s forward showcases her interest in “many types of femininity” with a particular concern for “good” Christian women. Similarly, in A Lady of King Arthur’s Court: Being a Romance of the Holy Grail, Sara Hawks Sterling is interested in giving a new female perspective to the legend. In her other work, Shakespeare’s Sweetheart, Sterling focuses on giving voice to the women in Shakespeare’s life (such as Anne Hathaway) and even includes a scene of same-sex desire between two women.

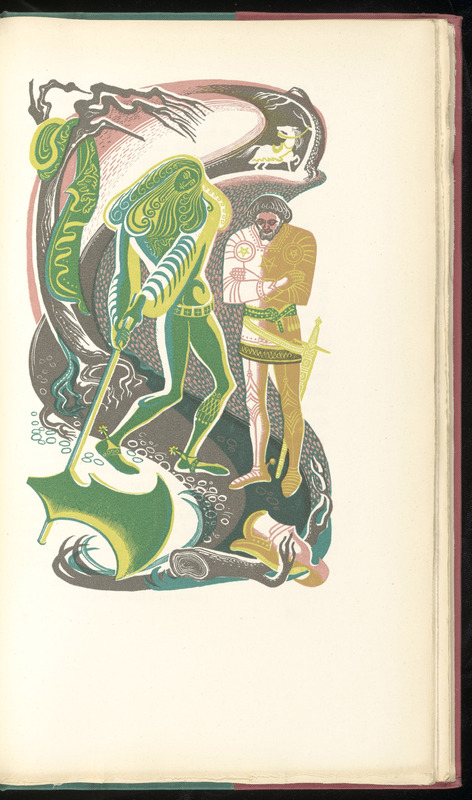

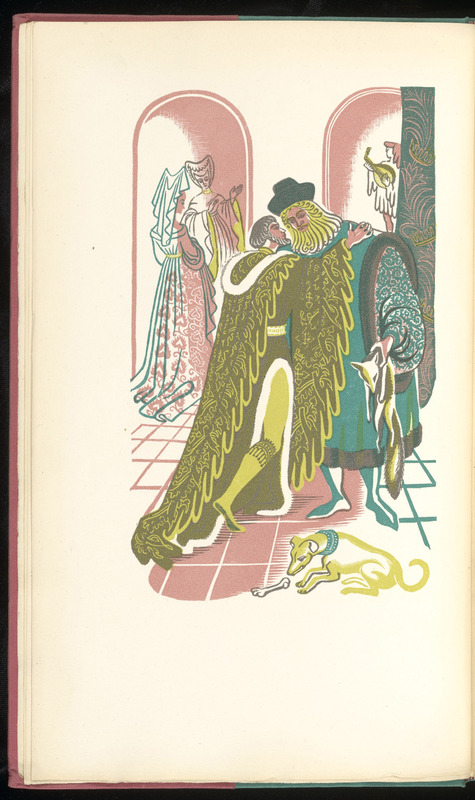

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, translated by Gwyn Jones, was published by Christopher Sandford at the Golden Cockerel Press, London, in 1952. Information surrounding the publication of the book reveals that the edition was limited to 360 numbered copies printed on Arnold’s mould-made paper in Caslon’s Old Face type with Pharos and Goudy Open titling. Gwyn Jones and Dorothea Braby worked closely together in discussing the details in each illustrated scene. Audiences aware of Cotton MS Nero A X, the only extant manuscript copy of the anonymous poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, know the manuscript contains four illustrations of the narrative. Braby creates six green and pink engravings that, according to art historian Muriel Whitaker, bring “antitheses basic to the text’s aesthetic pattern—warmth and coldness, natural and supernatural, courtliness and barbarity, sensuous castle life and rigorous forest hunts” (283). Braby’s figures are threatening, featuring “wintery branches [that] reach out skeletal fingers, the horse neighs in terror, and the enormous axe which the Green Knight is about to raise occupies the foreground” (283). Braby, like the original illustrator, creates a temptation scene between Gawain and Bertilak’s wife. However, Braby also shows an exchanging of gifts in which Gawain must kiss Lord Bertilak, highlighting the eroticism and queer desire that underlie the text.

Ref: Whitaker, Muriel A. The Legends of King Arthur in Art. Woodbridge, Suffolk: D.S. Brewer, 1990.