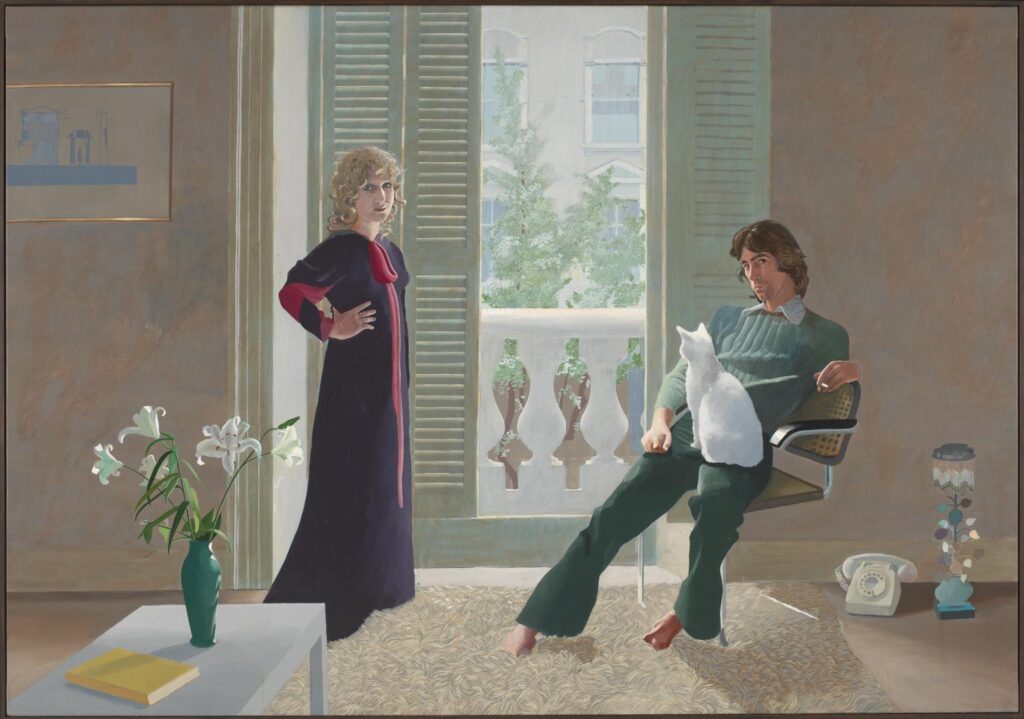

Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy 1970-1, by David Hockney. (Reproduction)

David Hockney’s “Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy” is an acrylic painting on canvas that is one in a series of large double portraits of couples. This particular painting is inspired by Hockney’s friends, fashion designer Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwel, a fabric designer. The couple are portrayed as timeless evident in that they wear an interesting combination of medieval crossed with 1970’s style clothing. The two lovers stare forward in a performative stance causing the “viewer, who looks at the painting from a central perspective, [to] be at the apex of the couple’s gaze out of the painting, a third in the relationship” (tate.org.uk, “Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy”) and participant in the performance of the piece. Though the couple poses in stillness in the comfort of their own home, there is an element of performance apparent in their stance, facial expressions, and in the strategic positioning of their bodies. Mrs. Clark’s strong, upright stance and Mr. Clark’s relaxed and open seated position is intentional and serves to “revers[e] one of the conventions of wedding portraiture, by seating the man while the woman stands” (tate.org.uk, “Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy”) and reexamine the performance of gender identity through physical positioning. This calculated positioning combined with the viewer becoming “a third in the relationship” through their interaction with Hockney’s piece serves to emphasize the significance of performance in everyday expressions of the self.